It's one of the best-known stories on campus. During a late night visit to Austin, a group of Texas Aggie pranksters branded the University's first longhorn mascot "13 – 0," the score of a football game won by Texas A & M. In order to save face, UT students altered the brand to read "Bevo" by changing the "13" to a "B," the "-" to an "E," and inserting a "V" between the dash and the "0." For years, Aggies have proudly touted the stunt as the reason the steer acquired his name. But was the brand really changed? And is that why he's called Bevo?

Sorry, Aggies. Wrong on both counts.

The last day of November, 1916 - Thanksgiving Day - was an eventful one for the University of Texas. At 9:00 a.m., a procession of students, faculty and alumni paraded south from the campus to the state capitol for the inauguration of Robert Vinson as the new UT president. Held in the House Chambers, students dressed according to their college and class. Seniors wore special arm bands, engineers sported blue shirts and khaki trousers, and freshmen huddled in green caps. There was enough pomp and oratory for the ceremony to last all morning.

After the inauguration, lunch was served on the Forty Acres. A boxed meal for twenty-five cents was available for those who wanted to picnic on the campus. Folks who preferred a more traditional Thanksgiving Day feast headed for the "Caf," an unpainted, leaky wooden shack that somehow managed to function as the University Cafeteria. The full turkey dinner cost fifty cents.

The afternoon was reserved for the annual football bout with the A & M College of Texas. A record 15,000 fans packed the wooden bleachers at Clark Field, the University's first athletic field, where Taylor Hall and the ACES Building are now. The first two quarters were a defensive struggle, and the half ended with the score tied 7 - 7.

During halftime, two West Texas cowboys dragged a half-starved and frightened longhorn steer onto the field, where it was formally presented to the UT student body by a group of Texas Exes. They were led by Stephen Pinckney (LL.B. 1911), who had long wanted to acquire a real longhorn as a living mascot for the University. While working for the U. S. Attorney General's office, he'd spent most of the year in West Texas assisting with raids on cattle rustlers. A raid near Laredo in late September turned up a steer whose fur was so orange Pinckney knew he'd found his mascot. With $1.00 contributions from 124 fellow alumni, Pinckney purchased the animal and arranged for its transportation to the University campus. Loaded onto a boxcar without food or water, the steer arrived at the Austin train station just in time for the football game.

After presenting the longhorn to the students, the animal was removed to a South Austin stockyard for a formal photograph and a long overdue meal. The steer, though, wasn't very cooperative. It stood still just long enough for a flash photograph, and then charged the camera. The photographer scurried out of the corral just in time, and both the camera and photograph survived the ordeal.

In the meantime, the Texas football team ran two punts in for scores to win the game 21 - 7.

To spread the news, the December 1916 issue of the Texas Exes Alcalde magazine was rushed into press. Editor Ben Dyer, BA 1910, gave a full account of the game and halftime proceedings. About the longhorn, Dyer stated simply, "His name is Bevo. Long may he reign!"

With the football season over, the steer remained in South Austin while UT students discussed what to do with him. The Texan newspaper favored branding the longhorn with a large "T" on one side and "21 - 7" on the other as a permanent reminder of the Texas victory. Others were opposed, citing animal cruelty, and wondered if the steer might be tamed so that it could roam and graze on the Forty Acres.

The debate was abruptly settled early on Sunday morning, February 12, 1917. A group of four Texas A & M students equipped "with all the utensils for steer branding" broke into the South Austin stockyard at 3:00am. There was a struggle, but the Aggies were able to brand the longhorn "13 - 0," which was the score of the 1915 football game A & M had won in College Station.

Only a week later, amid rumors that the Aggies planned to kidnap the animal outright, the longhorn was removed to a ranch sixty miles west of Austin. Within two months, the United States entered World War I, and the University community turned its attention to the conflict in Europe. Out of sight and away from Austin, the branded steer was all but forgotten until the end of the war in November 1919. Since food and care for the animal was costing the University fifty cents a day, and because the steer wasn't believed to be tame enough to roam the campus or remain in the football stadium, it was fattened up and became the barbecued main course for the January 1920 football banquet. The Aggies were invited to attend, served the side they had branded, and were presented with the hide, which still read "13 - 0."

Why did Ben Dyer dub the longhorn Bevo, instead of another name? For some time, the most popular theory has been that it was borrowed from the label of a new soft drink. "Bevo" was the name of a non-alcoholic "near beer" produced by the Anheuser-Busch brewery in Saint Louis. Introduced in 1916 as the national debate over Prohibition threatened the company's welfare, the drink was extremely popular through the 1920s. Over 50 million cases were sold annually in fifty countries. Anheuser-Busch named the new drink "Bevo" as a play on the term "pivo," the Bohemian word for beer.

However, while the Bevo drink was a long-term success, its sales in 1916 were comparatively small. Without the assistance of radio or television advertising, marketing campaigns were slower, and it took longer for retailers to buy in to the new Anheuser-Busch product. As it turns out, the Bevo beverage was almost unknown in Austin when Stephen Pinckney presented his orange longhorn to University students. Bevo the beverage just might be a red herring.

A recent suggestion made by Dan Zabcik, BA 1993, may prove to be the right one. Through the 1900s and 1910s, newspapers ran a series of comic strips drawn by Gus Mager. The strips usually featured monkeys as characters, all named for their personality traits. Braggo the Monk constantly made empty boasts, Sherlocko the Monk was a bumbling detective, and so on. The comic strips became so popular, that for a while it was a nationwide fad to nickname friends the same way, with an "o" added to the end. The Marx Brothers were so named by their friends in Vaudeville: Groucho was moody, Harpo played the harp, and Chico raised chicks when he was a boy. Mager's strips ran every Sunday in newspapers throughout Texas, including Austin.

In addition, the term "beeve" is the plural of beef, but is more commonly used as a slang term for a cow (or steer) that's destined to become food. The term is still used, though it was more common among the general public in the 1910s when Texas was more rural. The jump from "beeve" to "Bevo" isn't far, and makes more sense given the slang and national fads of the time.

Whatever the reason, UT's mascot was named by folks in Austin, not College Station.

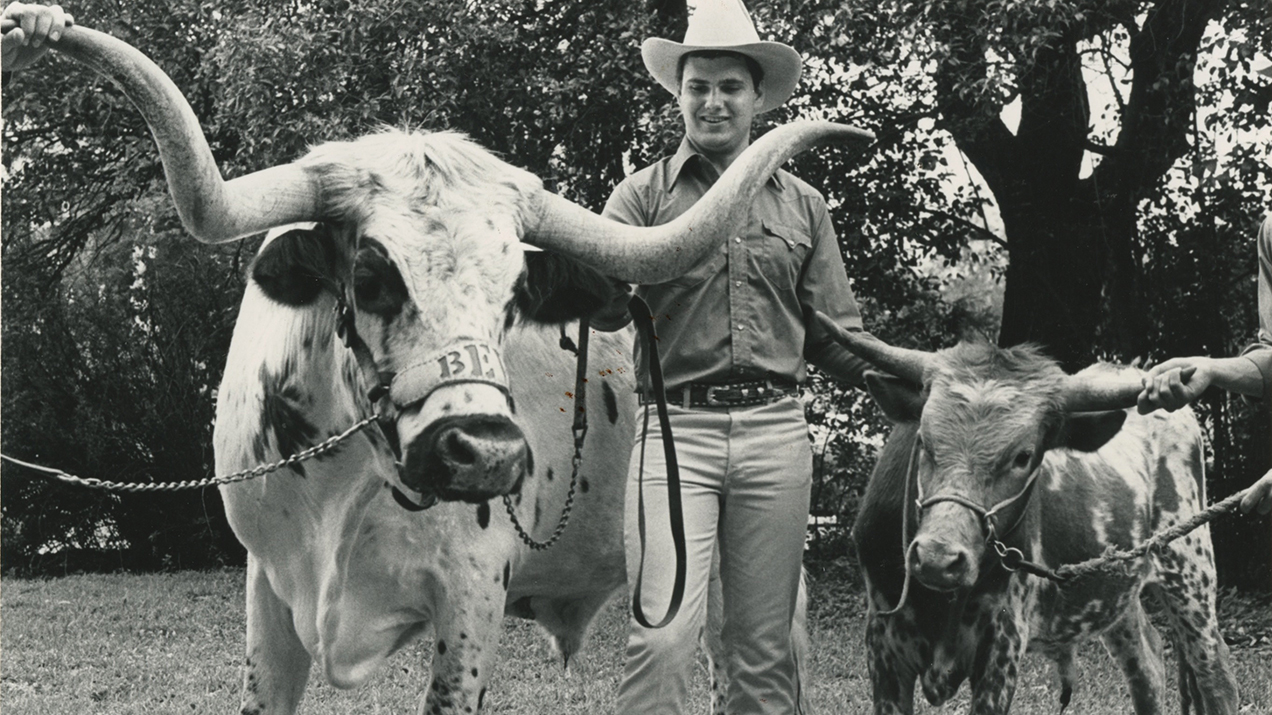

Former Mascot Pig Bellmont

"Hook 'em, Hounds?" While the longhorn steer named Bevo has been a symbol of UT athletics for over eighty years, the university's first mascot was a scrappy tan and white dog named Pig Bellmont.

Born in Houston on February 10, 1914, Pig was only seven weeks old when he was brought to Austin by L. Theo Bellmont, a co-founder of the Southwest Athletic Conference and the University's first Athletic Director. Not long after his arrival, Pig was adopted by the University community, and for the next nine years roamed the campus as the 'Varsity mascot.

Every morning, Pig greeted students and faculty on his daily rounds. He frequented classrooms, and on cold days even visited the library (now Battle Hall). Pig regularly attended home and out-of-town athletic events, and it was said he would snarl at the slightest mention of Texas A&M. During World War I, Pig looked after the cadets of the School of Military Aeronautics, which was housed on the campus. He never missed a hike, and was always present for inspection. At night, Pig retired to his favorite digs under the steps of the University Co-op.

Pig was named for Gus "Pig" Dittmar, who played center for the football team. Gus was known to slip through the defensive line "like a greased pig." During a game in 1914, the athlete and the dog stood next to each other on the sidelines, and students noticed that both were bowlegged. It was not long before the dog had found a namesake.

On New Year's Day, 1923, Pig Bellmont was hit by a Model T at the corner of 24th Street and Guadalupe. He was only injured, but no one realized how seriously until his body was found a few days later. Pig's death was a tragic event on the campus, and the students decided to pay a final, fitting tribute to their canine friend.

On the afternoon of Friday, January 5th, Pig's body lay in state in front of the Co-op. Hundreds of mourners doffed their hats and filed by Pig's black casket, which was draped with orange and white ribbon. At five o'clock, the funeral procession began. Led by the Longhorn Band, the group marched south on Guadalupe Street to 21st Street, then east to the old Law Building, where the Graduate School of Business now stands. Pig's pallbearers were members of a new student group called the Texas Cowboys.

Northwest of the Law Building, under a small grove of three live oak trees, Pig's eulogy was delivered by Dr. Thomas U. Taylor, Dean and the founder of the College of Engineering. "Let no spirit of levity dominate this occasion," the Dean began, "A landmark has passed away." Pig was praised for his loyalty to the University, and compared to the faithful dog of Lord Byron. "I do not know if there is a haven of rest to which good dogs go, but I know Pig will take his place by the side of the great dogs of the earth." On cue, following Taylor's speech, a lone trumpeter played Taps in front of the Old Main Building.

After the funeral, a marker was left to remind the students of their first mascot. His epitaph: "Pig's Dead . . . Dog Gone."